Montessori Research

Parents naturally want to set their children up for success, so they ask tough questions in order to make an informed choice when deciding amongst educational programs. For a Montessori school, people often want to know:

How does this educational framework compare to others?

Will my child get the knowledge they need to be successful adults?

Is this method the best fit for my child?

While we would always welcome more in-depth academic research to support the work that we do at Mountain Sun, there is good data out there! Here are some of the most striking findings:

1. A Montessori program for early childhood education leads to greater success down the road.

The research presented here suggests that a “classic” Montessori preschool program - that is, one that closely follows the recommendations created by Dr. Maria Montessori in the early 20th century - “is associated with significant gains in student achievement and development.”

Angeline Lillard is well-known for her studies of Montessori education. “She and Nicole Else-Quest tested one set of children after they completed primary education, at around five years old…On a variety of tests, ranging from letter-word identification to math, these Montessori kids outscored their public school counterparts.”

Interestingly, these two researchers also followed a group of 12-year-olds in the same study that ended up performing equally as well as their peers in traditional school programs, but not higher. "What is notable regardless is that they're not doing worse than their peers despite the fact that they weren't being tested repeatedly on multiple-choice-type tests," reported Lillard.

Children in early Montessori programs have also been found “to use more mature social problem-solving strategies, particularly ones centering on justice and taking another person's goals into consideration…” This finding is significant because “social competence in preschool is associated with better outcomes in social and academic domains.”

Lillard also measured these social developments. “When confronted with social issues, such as another child hoarding a swing, participants more commonly resorted to reasoning - 43 percent to 18 percent. And on tests of so-called executive function (the ability to adapt to changing rules that increase in complexity) Montessori children again outperformed their peers.”

Another study notes: “To be successful takes creativity, flexibility, self-control, and discipline. Central to all those are executive functions, including mentally playing with ideas, giving a considered rather than a compulsive response, and staying focused. This comparison study of curricula shows that the Montessori approach meets more criteria for the development of executive function for a more extended age group than other methods.”

We can conclude then, as Lillard has, that the scores from children in these Montessori preschool programs, is certainly meaningful. “Gains of this magnitude early in life would be expected to have lasting benefits to children and society.”

2. The Montessori method develops a child’s executive function, which is a major predictor of academic success.

Think 21st Century Skills. Think Emotional Intelligence. Think Paul Tough. These are all examples of growing a child’s executive function. At Mountain Sun, it’s our holistic approach to education. “Research shows that students who attend Montessori schools foster higher levels of executive functioning skills like self-discipline, autonomy over learning, deep focus, critical reasoning and problem solving.”

"’I think a Montessori background is better for developing an entrepreneurial skill set,’ said a Montessori alum and web designer. Since much of the learning process is self-directed, children can gain a sense of independence and confidence in their abilities much faster than in a traditional school setting.”

From Lillard’s breakthrough study: “Executive function is an umbrella term covering several component skills, such as working memory, inhibitory control, attention, planning, and flexibility. It is sometimes viewed as redundant with self-regulation. Executive function skills are significantly related to children's success in school as well as social skills.”

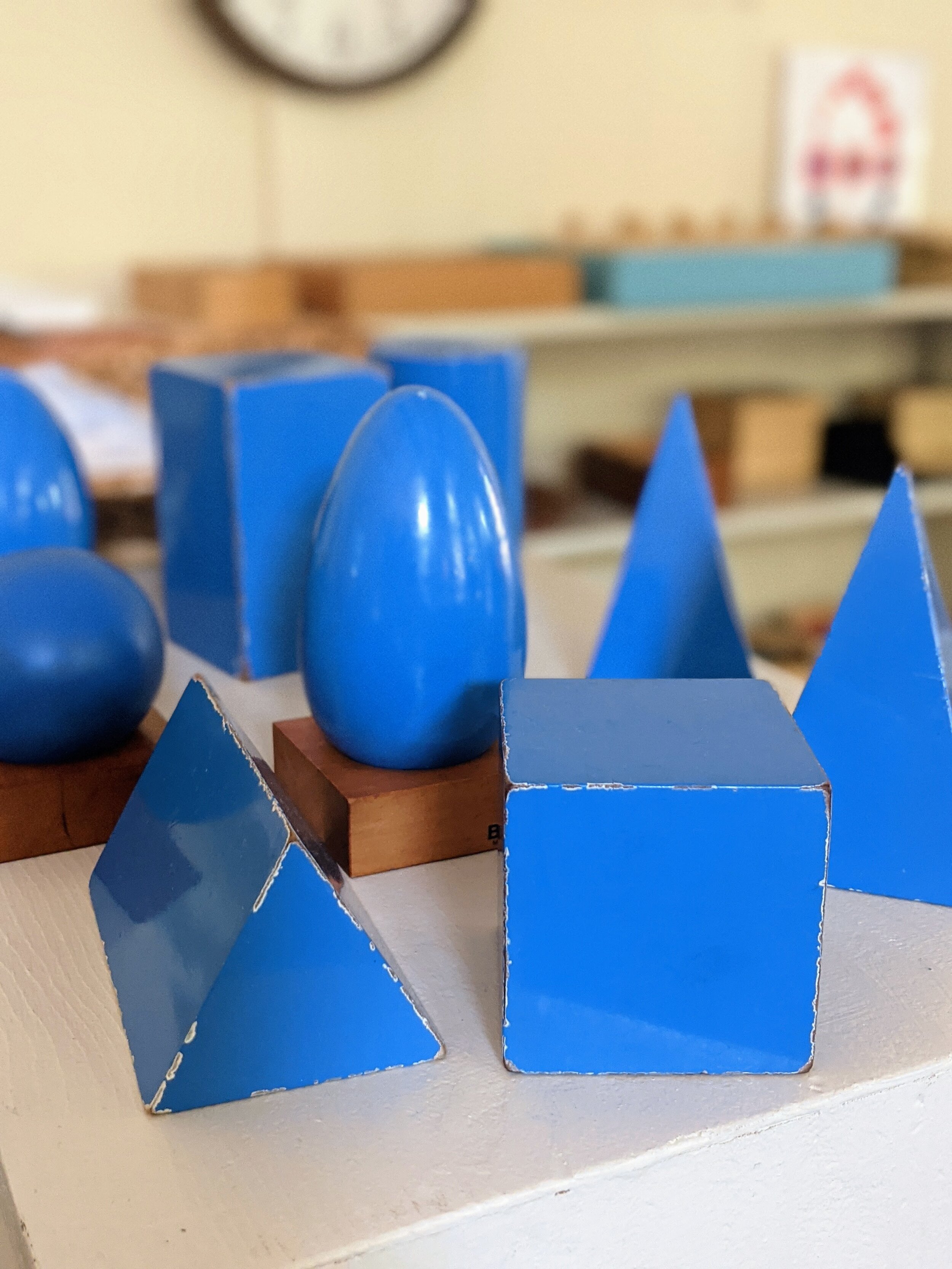

“Theoretically, using Montessori materials would seem to exercise many aspects of executive function,” says Lillard. Take this example where she evaluates the Pink Tower, a common Montessori building block tool: “In using this material, the children's task is to carry the cubes one by one from a display to a rug that they have previously rolled out on the floor, then rebuild the tower. To do this task entails planning. Second, each time a child chooses a block, she or he must do so with reference to its relation to all the other blocks: Is there another one in between the size of this one and the last one placed on the tower? This step requires working memory. Third, the child must inhibit the prepotent tendency to grab the closest block, and fourth, the child must pay strict attention to how he or she places each block on the one below it, creating a symmetrical tower. After building the tower, the child takes it down, returns the blocks to their stand by the shelves (in the proper order), and then tightly rolls up the rug and returns it to its place. This step requires flexibility and task switching.

“Consider the difference between this and engaging with ordinary blocks. With ordinary blocks, one can do anything, without necessarily having any set plan, and one does not have to think about the blocks in relationship to each other. A traditional preschool might not have a requirement that children put items away right after use (instead, there often is a single clean-up time right before going home), and there may well be no set way to arrange blocks when returning them to their place (often, they get put haphazardly into a large basket or box). The executive function demands are much reduced, and this difference in executive function demands applies across many other activities as well.”

Gains in executive function are important “because children with stronger executive function skills in kindergarten are concurrently and subsequently more academically and socially competent. Increasingly, executive function skills are seen as key not only to school readiness but to success in life.”

Is there an association between children’s levels of self-regulation and academic achievement in Montessori and non-Montessori classrooms? A study done in South Carolina found that Montessori children have comparatively higher levels of self-regulation and more consistent growth in self-regulation skills over the 3-year period of the study than non-Montessori students. “Their scores on the MAP (Measure of Independent Progress) standardized tests also indicated higher abilities in both reading and math, leading to the conclusion that there is a direct relationship between levels of self-regulation—particularly on work habits where the ratings for Montessori children were shown to be statistically significant—and academic achievement when analyzing the results of that one test.”

Interview data from that same study shows that “Montessori children, by the end of second grade, understand that work is hard but that practice and working with materials are the essentials for understanding. Learning habits of practice and work, so much a part of the culture of Montessori classrooms, may be another reason why Montessori children achieve academically. The conclusion is that there is an association between how well children internalize levels of self-regulation and their academic success.”

3. Montessori teaching methods and tools lead to higher test scores, especially in math and science.

Our job as educators is to prepare our students for their future in the world. At Mountain Sun and in many Montessori schools, we do this through a combination of state-based standards and techniques that inspire children to want to learn. As Lillard’s research above again points out, a Montessori education can produce gains in academic achievement and “school readiness” as early as 5-years-old.

“In essence,” one study found, “attending a Montessori program from the approximate ages of three to 11 predicts significantly higher mathematics and science standardized test scores (specifically the ACT and WKCE Wisconsin state exams) in high school.” Close to home, another study from South Carolina found that a greater percentage of Montessori students in grades three through eight passed reading and math assessments than their traditional school peers. This was true for every year of the 5-year study (Moody, M. J., & Riga, G. (2011). Montessori: Education for life. In L. Howell, C. W. Lewis, & N. Carter (Eds.), Yes we can!: Improving urban schools through innovative education reform (pp. 127-143). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.)

Much of the gains in math scores are thought to be tied to the key Montessori method to prepare the environment. “Creating a beautiful and accessible environment is of paramount importance, as children direct their own learning with the help of meticulously designed learning aids,” says a founder of an international Montessori school in Japan. And as this school explains very well, “Montessori math materials help children approach math with hands-on, visual, and physical learning aids. These materials allow students to attach concrete knowledge to the often abstract concepts in math.”

Another study noted that while there was not a significant difference with regards to a student’s ability to solve math tasks, Montessori students demonstrated more flexible, conceptual thinking in their approach to solving these problems (Reed, M. K. (2008). Comparison of the place value understanding of Montessori elementary students. Investigations in Mathematics Learning, 1(1), 1-26.) As we covered in Question #2, this thorough approach to thinking can have long-lasting benefits to success in adulthood.

Findings on reading and writing gains in Montessori programs are not as dramatic or extensive, but they also exist. From Lillard: “the gains in letter-word identification scores for the children in classic Montessori programs were twice what they were for the other two study groups (11 vs. 5–6).” And at the end of elementary school, Montessori children wrote more creative essays with more complex sentence structures.

Montessori is not the answer for everyone or every program. But if it is the right fit for your family, it’s good to know that data proves equal - if not greater - success for students educated using the Montessori method. “Montessori education fosters social and academic skills that are equal or superior to those fostered by...other types of schools,” says Lillard, once more.

“One of the main questions we get is if our students are at grade level,” said Becky Langerman, our Director of Learning. “There's a misconception that our students are ‘behind.’ This could be the case if they leave midway through a 3-year grade cycle and are put into a more traditional setting. However, if they stay the course - especially through middle school - they certainly show advanced skills.”

As many of the researchers and studies mentioned here point out: we need more research! Montessori is a method that has been around for 100 years and should be seriously evaluated. And when institutions undergo the process of improving both educational theories and preparedness for a successful adulthood, we hope that Montessori education will be a part of the equation based on its proven success rate, especially in early childhood education. “As...educators search for ways to improve the academic and social outcomes of children in American schools, Montessori education might be worthy of more consideration.”